The State of Continual Welcoming

August 20, 2025

Will we ever be done talking about AI? Of course many artists are worried. Those whose work can be automated are worried that their jobs — even their sense of purpose — will be automated away. With respect to art, I’m not very concerned.

After a long and somewhat unbearable slow period of creativity, I have, as my friend Andy says, “struck a vein.” I’m excited to get into the studio to keep mining this vein, moving forward, liking where things are going, and enjoying the ride. I think this is what making art is all about — finding that space where you’re in sync, when things just work, and occasionally you even surprise yourself. When I make myself laugh out loud while working on a piece, I know I’m in the right place. And I try to stay there as long as possible, but eventually, it always ends.

It’s impossible to know when these highly productive periods will arrive and how long they will last, since they depend on so many factors outside our control. As Rick Rubin says:

"We cannot force greatness to happen, all we can do is invite it in and await it actively, not anxiously, as this might scare it off, simply in a state of continual welcoming."

That’s easy to say, but hard to practice. Staying in that state of continual welcoming is tough. There are always distractions, diversions, detours pulling us away. But when inspiration strikes, and that juicy vein reveals itself, it’s go time!

Today, while riding my bike, I was thinking about this new work I’m making — and why I like it. I realized it comes from a kind of cumulative, slowly evolving Venn diagram, where many of my different long-term influences gradually overlap, eventually revealing that sweet little bullseye in the middle:

My lifelong love affair with the mountains.

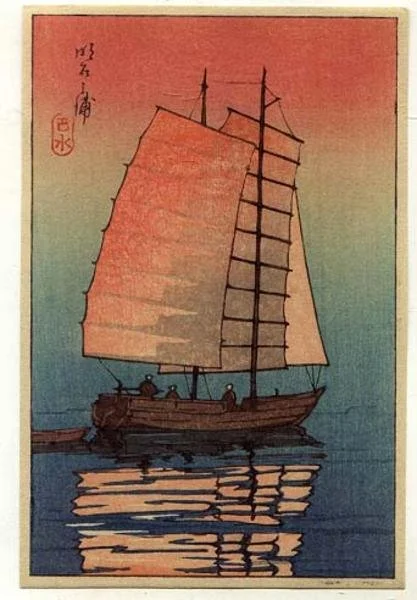

The soft, precise, sensual quiet of Hasui Kawase’s woodblock prints.

The irreverent, graphic, psychedelic-pop of Tadanori Yokoo.

The analog wholesomeness of Roy Lichtenstein’s paintings.

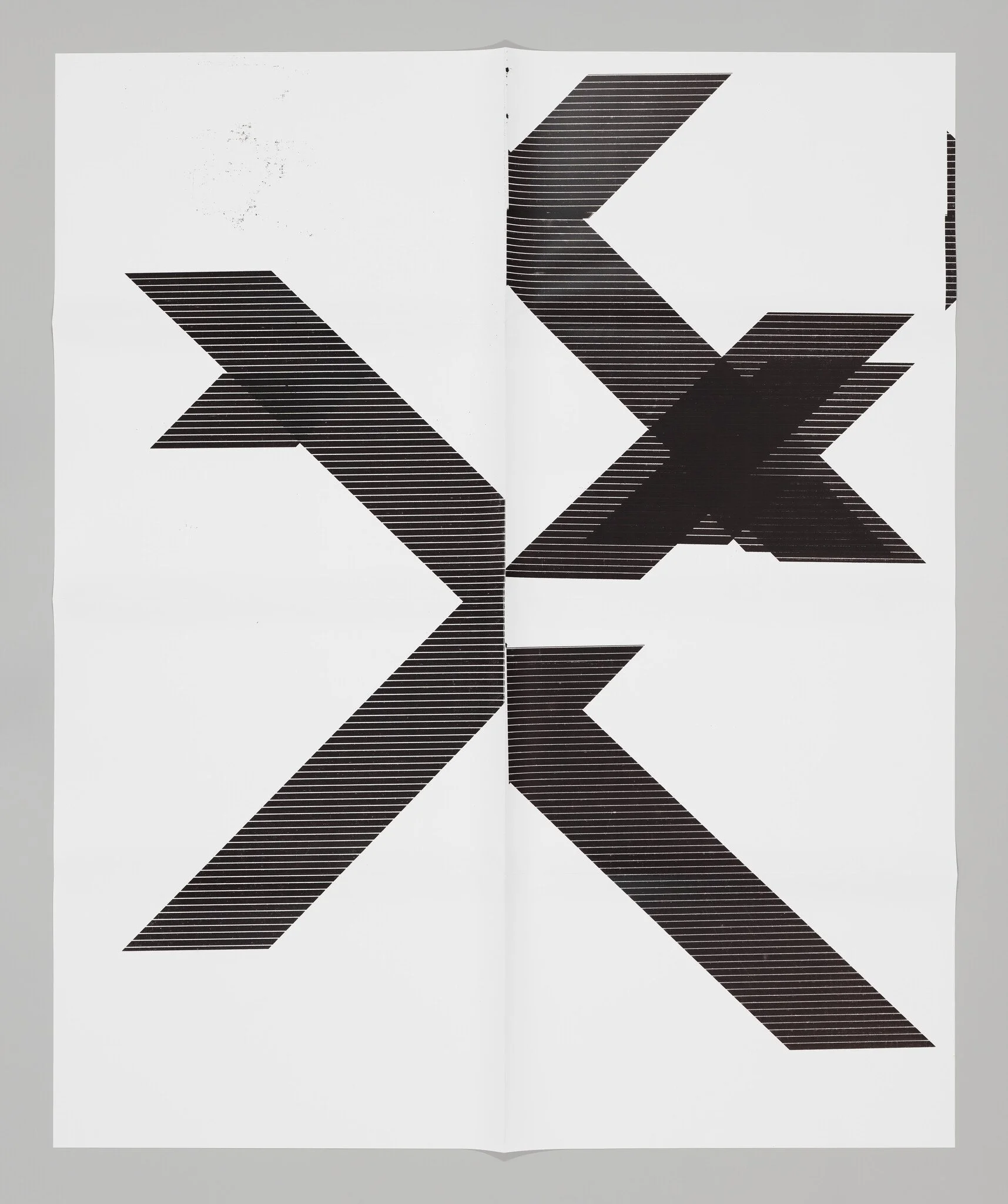

The glitchy brokenness of Wade Guyton’s inkjet prints.

Above: Hasui Kawase, Tadanori Yokoo, Roy Lichtenstein, Wade Guyton

Everything in this list connects to a specific, in-person mind-expanding experience that stuck with me. I’ve seen the works of all of these artists up close — felt their energy, absorbed them, and saved them to my mental hard drive in the root folder, with a backup for protection.

A few weeks ago, I went back through decades of mountain photographs from skiing, biking, hiking — images from the US, Canada, Europe, Japan, China. I revisited books of Kawase, Yokoo, Lichtenstein, and Guyton. Then I started mashing everything together, following my instincts for composition and color, just to see where it went.

Eventually I realized this work had a few common denominators. The mountain images are rooted in strong, personal experiences in nature that can’t be recreated any other way. These other artists are also deeply rooted in the analog: carved wood, ink and water (Kawase) lithography and silkscreen (Yokoo); hand-painted Ben-Day dots from comic books (Lichtenstein); the random beauty of a misaligned or clogged inkjet printhead (Guyton).

But working digitally on this project feels right for now. It lets me layer, experiment, and adjust in ways that reference those analog techniques without needing to imitate them. I suppose I could try to produce a lithographic woodblock silkscreen with finely hand painted details that is ultimately jammed into an inkjet printer for a final pass? Sometimes the right tool for the job the obvious one.

My most recent piece was made using images I shot on three different trips over two decades. If you ski at Alta or A-Basin, you may recognize parts of this. For now, it’s my most favoritest. It combines real human experience in a way that is meaningful to me, because I was there:

Which brings me back to AI. What I’m doing with this project is, on the surface, not so different from what AI does, and what ALL art-making humans do: it takes source material, mashes it up, and produces something new. But here’s the difference: my mashup is mine. It’s rooted in experiences that happened to me in the real world — being alone in the mountains, feeling the peace and solitude, standing in front of these artworks, absorbing their energy. That’s something AI will never have.

We connect with art made by humans for the same reasons we can’t have a meaningful relationship with a salad bowl. Art is rooted in human experience — somethign a computer will never have.

Out of curiosity, I tried asking ChatGPT to generate an image inspired by these four artists, just to see what would happen. Of course, using names triggered copyright concerns. So I watered the prompt down to something vague, like:

"A dreamlike mountain scene with soft flowing gradients and intricate details. Vivid, surreal bursts of color and geometric forms overlay the landscape, contrasted with tiny patterned textures in select areas. Gentle imperfections ripple through the image — faint streaks, faded patches, and misaligned color layers — creating a balance of the organic and the mechanical."

After a few more revisions, I found a prompt that worked:

“Peaceful mountain landscape with many layers, colored with soft gradients in some parts, tiny dots like those in comic books in others, overall the color palette of the pyschedelic 1960's, and some parts of the image that look like it was made by a failing inkjet printer with a misaligned print head.”

Which passed the copyright policy test. Here’s what I got:

It’s not just bad. It’s….dead. It has no soul. If you could cut this open with a knife it would be full of dead black goo. I’m not interested in making work this way, or looking at work that is made this way.

Someday (probably very soon), copyright concerns may ease and people will use AI to make works in the likeness of any artist. But an original work by a human artist will always and only be theirs.

AI can remix, but it can’t live.